I saw this morning that the number of reported measles cases in the US has reached a 33-year high. About 1300 cases have been confirmed. That made me decide to write a companion piece to the podcast episode we released last Thursday with Dr. Jay Butler, the former Deputy Director of Infectious Disease at the CDC. We thought we might post it on the BioLogos website, but things are backed up there with lots of new things in the offing. So I’m putting it here instead.

Most of our Language of God recordings still take place remotely, so when I learned that Jay would be in Grand Rapids for a conference, I jumped at the chance to sit down with him in real life. BioLogos president, Kristine Torjesen, and I first met him for breakfast at a local diner, and the two of them lamented about their recent disheartening experiences related to drastically reduced federal funding of medical research. Then back at the BioLogos office, tucked into our small studio with the microphones on, it was my turn.

It was fun to see Jay’s face rather than an avatar on a computer screen. He was warm and funny and disarming, but what struck me most was a line that recurred throughout our conversation: public health, Jay said, is ministry. “I came to see the face of Christ in surveillance data,” he told me, quoting Matthew 25’s vision of serving Christ wherever the vulnerable are found.

That sentence encapsulates why BioLogos keeps repeating the simple refrain, “science is good”, which I highlighted in these pages two months ago. Science—especially the kind that prevents disease and relieves suffering—isn’t a secular distraction from spiritual life. It is a God-given tool for obedience and love. And the three parables of Matthew 25 give us a compact theology for deploying that tool today.

1. The Wise and Foolish Bridesmaids: The Wisdom of Preparedness

In Jesus’ first parable, ten bridesmaids wait for the bridegroom. Five keep their lamps trimmed and their oil stocked; five let the light sputter out. Wisdom, in other words, plans ahead. Jay reminded us just how demanding that kind of preparedness is when the adversary is a virus as contagious as measles. Its basic reproductive number (R₀) hovers between 12 and 18, meaning a single case can ripple outward with explosive speed. To halt transmission we need about 97 percent of the population immune—a target that a single dose of MMR can’t quite reach.

Hence the two-dose schedule now recommended for every child. Vaccination, like having your lamp filled with oil, is an act of anticipatory love: you prepare before the disease sweeps through the village. In an age when misinformation urges us to blow out the lamp entirely, the parable calls us back to the wisdom of common sense of prevention.

2. The Talents: Stewarding Scientific Gifts

The second story in Matthew 25 is about servants entrusted with their master’s property. Two invest and multiply the treasure; one buries his coin in the ground. Jay walked us through the human equivalents of those investments: Maurice Hilleman’s painstaking attenuation of the Edmonston strain of measles virus, the decades of field trials, and the eventual combination into the MMR vaccine.

The yield on that investment is staggering. Between 1974 and 2004, childhood immunization is estimated to have saved 94 million lives from measles alone. Every lab technician who titrated a viral culture, every epidemiologist who chased an outbreak, every nurse who calmed a frightened toddler in the clinic was doubling the master’s silver. To bury those talents—by defunding research, eroding public-health infrastructure, or dismissing scientific expertise—seems perilously close to the fearful servant’s inaction that Jesus condemns.

3. The Sheep and the Goats: Mercy to the Least of These

Finally, Jesus pictures the nations gathered for judgment, sorted by whether they recognized him hungry, thirsty, naked, or sick. If statistics in public health are “people with the tears removed”, as the quip in the industry goes, Jay doesn’t want to lose sight of the weeping people—real neighbors whose names rarely make the news.

The MMR series protects me, but it also protects the immunocompromised child in my church who cannot form antibodies, the elderly neighbor on chemotherapy, the newborn too young for her first shot. Herd immunity is mercy in microbial form, extending a shield to those who cannot lift one themselves. When we choose to opt out—especially for reasons untethered from evidence—we quietly shift a very small personal risk onto the shoulders of those least able to bear it.

Breakfast Epilogue: Funding, Trust, and the Call to the Church

Over breakfast Jay and Kristine mourned the drastic reduction in funds for public health. The recent dismissal of the entire federal vaccine advisory panel at the CDC has only deepened the crisis of trust. Jay worries that providers who once depended on those consensus guidelines of these experts will now wonder whom they can believe.

Here the church has both an opportunity and a responsibility. The opportunity is relational: congregations remain one of the few places in American life where people of divergent ages, incomes, and political persuasions still form a community. We can host vaccine clinics, invite local epidemiologists to adult-education hours, or simply accompany a nervous single mom to the health department. More profoundly, we can model a posture of curious humility—asking questions without presuming scandal, weighing evidence with charity, and refusing to baptize partisan talking points as gospel.

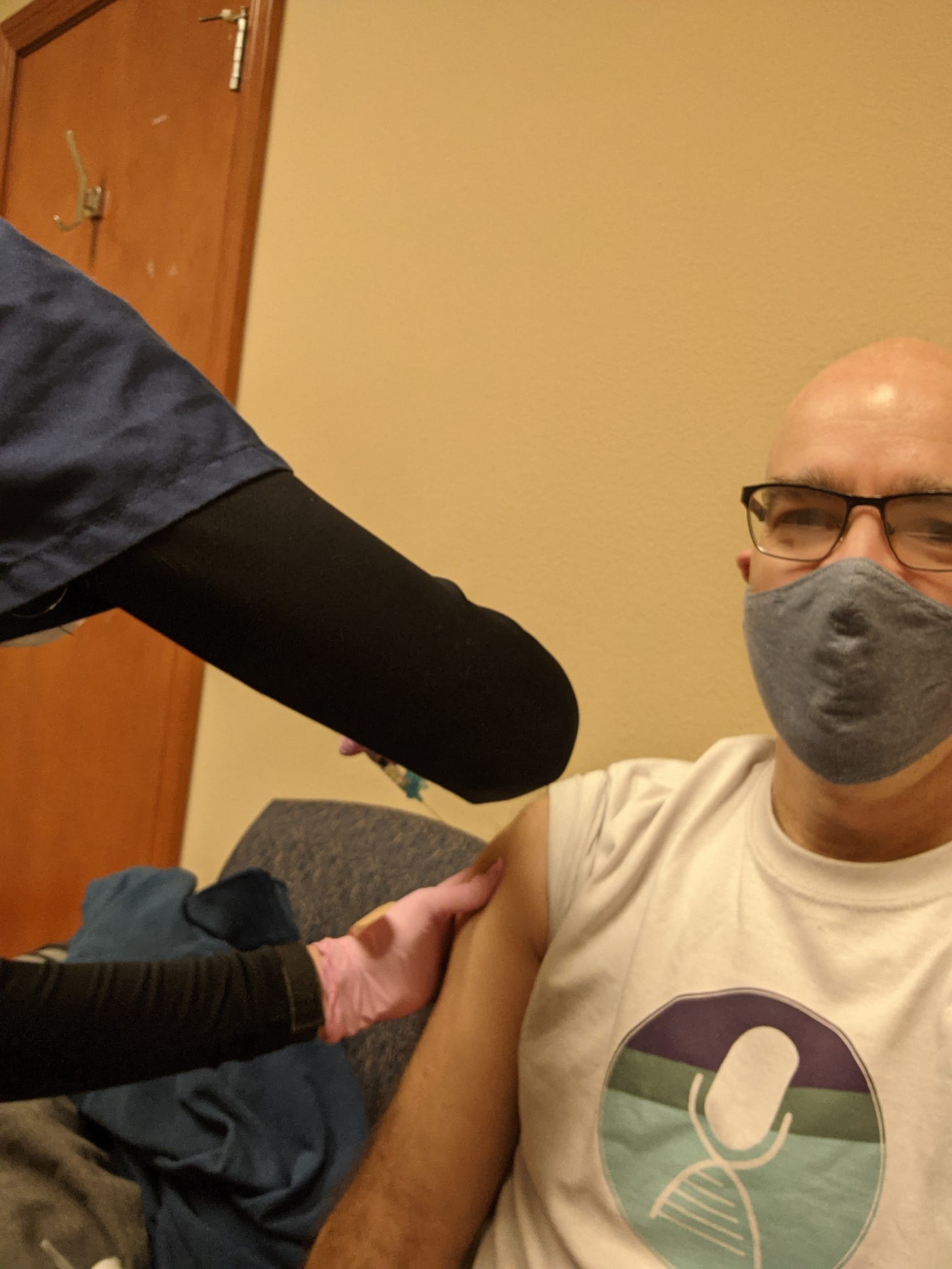

Our responsibility, meanwhile, is to remember that love of neighbor sometimes looks like a Band-Aid on the upper arm. When Jesus says, “I was sick and you visited me,” he does not specify whether the visit happened in an ICU or a county-run vaccination site. Either way, the encounter is sacramental.

Science Is Good… When We Use It Well

I came away from our conversation convinced anew that science and faith working together in the field of public health looks a lot like Matthew 25. Science offers reliable knowledge and innovative tools; faith supplies the vision that directs those tools toward justice and mercy. The wisdom of preparedness, the stewardship of talent, and the compassion for the least of these—each finds concrete expression when a trained chemist formulates a vaccine, a logistics manager delivers it to a rural clinic, and a pastor spends his Sunday afternoon holding kids’ hands in the waiting line.

That is why BioLogos keeps telling stories like Jay Butler’s. They remind us that “science is good” is not sloganeering but testimony: testimony that our Creator’s world is intelligible, that our minds are meant to explore it, and that our discoveries can be folded back into the great work of love.

So keep your lamps filled, invest your talents, and look for Christ in the public-health dashboard. The next breakthrough—against measles, malaria, or the misinformation virus—may come from a lab bench or a church basement. May we be found ready!

Jim, another beautiful post, this one really needed to be said. I am totally astonished at the current trend of people to fall into ideas that are destined to cause them great harm. This is now true on all parts of the political spectrum. I remember seeing a list of dozens of radio preachers who had railed against vaccines, until their voices were forever stilled by death from COVID. The horror of the stories from friends in medicine about patients begging to be given the vaccine. The nurses had to be trained how to tell them, "Sorry it's too late now". I will stop here. Bless you Jim.

Amen