Metaphors for Science and Religion

A SJHS Story

I like a good metaphor. The business of science and religion has lots of them to try to explain how these two different ways of knowing might be related. The oldest (and probably the most popular) of these is the “Two Books” metaphor: the book of God’s word and the book of God’s works. That is, the Bible and nature. The way the explanation goes is that God is the author of both, and so they must agree. Problems come when we finite-minded humans try to interpret both books by doing our theology and our science. I’m not sure authors are always consistent from book to book, especially when the genre is so different, but I get the point.

The interesting thing to me about the Two Books metaphor is that it used to be justified by saying, “Look, not everyone can read, so God has also communicated to us through nature, where everyone can see the message.” Nowadays, though, that has reversed: now we’d say not everyone can be a scientist and learn the secrets of nature, so God made sure everyone would have access to the message and so gave us a literal book to read. Literacy rates are pretty high now… but what do you suppose the rates of sound interpretation are?

I think a better metaphor for science and religion is maps. Maps work because they abstract some information — but not all information — from a particular area and represent it. A map that gave all the details of the reality it is representing would not be useful. Think of going to a new city and seeing the subway map, which shows a diagram of the stops of different trains, but not necessarily drawn to scale. It wouldn’t be that helpful if you were out walking the streets and trying to find a coffee shop. And a topographical map shows very different information about the area. Depending on what information you need about the area, you’ll select the appropriate map to use.

So too with science and religion. If you want to know the question of how photosynthesis works, religious texts and traditions aren’t going to be much help. If you want to know if slavery is wrong, science isn’t going to be much help. Science is a very good map to the empirical and quantifiable aspects of the world. Religion can be a good map to finding meaning in the world.

The difficulty here is that it can seem like science and religion are kept completely separate (the independence model, if you’re familiar with Barbour’s typology). Lots of times science and religion do function independently of each other, but there are some questions that need both. For example, what does it mean to be human?

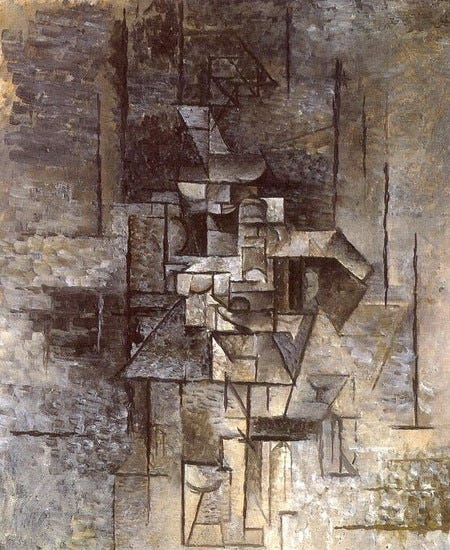

In the section of the book I’m writing, I wanted to use an artistic metaphor in a way that would work for science and religion both being relevant to particular question. Here’s what I came up with: science and religion are like different styles of painting. Consider these two paintings by Picasso: The Old Guitarist and La Mandoliniste.

Both are representations of someone playing a guitar, but they understand that object very differently. The Old Guitarist, from Picasso’s Blue Period of expressionism , shows an emaciated figure hunched over his guitar, bathed in sorrowful blue hues. It evokes a mood more than attempting to replicate an object in the world. Through this picture of someone playing a guitar we are seeing the world through the lens of profound melancholy.

Then consider La Mandolinista from Picasso’s later Cubist phase. I won’t pretend to understand all the subtleties of cubism, but I gather that it attempts to distill a figure — a person playing a guitar in this example — down to its most fundamental forms and present these from multiple angles. We no longer see a single, sorrowful musician. Instead, we perceive a fragmented reality that challenges our assumptions about space and form. The guitar and guitarist are still there, but they are reimagined, dissected, rearranged.

This might be similar to how science and religion attempt to make sense of the human condition. Both are relevant and get at important aspects of us. But neither tells the whole story, and neither is simply recreating their objects. Furthermore, they are not competing accounts of reality, as if the truth of one painting means the other must be false. Each reveals certain truths that might remain hidden if we only looked through a single lens.

What do you think? No metaphor is perfect, but does this work? And since both these paintings are in the public domain, can I reprint them in my book?

Good examples. Interestingly, I have been thinking of a metaphor that I am presently living, what with Easter nearing and all, and have been thinking of writing a bit about it. I had my prostate removed for prostate cancer last July, and while the biochemical markers show it gone, due to the aggressive cell type am taking hormone blockers and undergoing radiation. In other words, my body seems free of cancer, but an undergoing treatment that is pretty destructive and invasive in the promise of eliminating that which is unseen, and hopefully giving more life later. The metaphor, which I hope does not border on diminishing Christ's sacrifice, is of Christ sacrificing his sin-free body to eliminate the cancer of sin on humanity, and the agony of that decision that weighed on him in the garden, much as the agony of willingly undergoing a destructive treatment for an unseen cancer weighs on me. If nothing else, it has made Christ's cry to remove that cup more poignant to me.